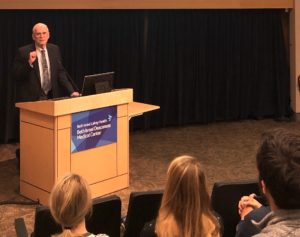

In January 2020, J. Thomas Lamont, M.D. (author of C. Diff In 30 Minutes) gave a grand rounds presentation at the Sherman Auditorium, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. He was looking back at Major Advances in Gastroenterology & Hepatology over a 50+ year period, which actually stretched back to a much earlier age of scientific and medical discovery. From the introduction by Nezam H. Afdhal, MD, the current Chief of the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition at BIDMC:

In January 2020, J. Thomas Lamont, M.D. (author of C. Diff In 30 Minutes) gave a grand rounds presentation at the Sherman Auditorium, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. He was looking back at Major Advances in Gastroenterology & Hepatology over a 50+ year period, which actually stretched back to a much earlier age of scientific and medical discovery. From the introduction by Nezam H. Afdhal, MD, the current Chief of the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition at BIDMC:

[Lamont] published a paper that was the cover of Nature that illustrated why the stomach does not digest itself due to the interactions of mucins and the effect of acid on the mucin structure within the stomach. At BIDMC he and his research team worked on the mechanism of action of the toxins for C. difficile. These are just some of his scientific advances. He is a clinician, still sees patients today, and is a well sought after teacher, and has educated innumerable fellows and faculty. He’s been a mentor to many. He’s been a great friend to the GI division here at BIDMC. His lecture this morning is going to be a look back at what has happened in the 50 years of Tom’s career in gastroenterology.

Here is the full presentation with audio, about 45 minutes long:

Some selected quotes by Lamont follow. You can view a full transcript of the Lamont’s Grand Rounds presentation here.

On incremental progress vs. paradigm shifts:

I used to think, and a lot of people believe that discoveries are incremental, that knowledge is added like bricks to a wall which you gradually build. But in fact scientific discoveries are primarily revolutionary not incremental. There’s a paradigm shift which is a radical change in the way we do things. It’s often disruptive, a word borrowed from technology, where the new discovery or invention blows up whatever was there before. Later in the talk I’ll show you some examples of disruptive discoveries and inventions in the field of Gastroenterology.

On convincing the scientific establishment:

A major feature in the field of scientific discovery is resistance from the establishment. I can tell you that Boston has a very powerful medical establishment, and the resistance to some of what I’m going to show you was quite robust. So, if you’re interested in this topic, there’s a very important small book, about 100 pages long, by Thomas Kuhn called “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions”. Kuhn championed the concept of paradigm shift, in which scientists have to move away from something that has been accepted for a long, long time. And the new paradigm replaces the original paradigm, which eventually fades away.

On technology transfer from other fields:

Kapany and colleagues then had the idea that extremely thin flexible glass fibers could transmit endoscopic images. This was picked up by Basil Hirschowitz, a native of South Africa, who in 1953 was a GI fellow at the University of Michigan. He was already trained in endoscopy in England before he went to Michigan. Hirschowitz was trained in the Schindler type of endoscopy that I showed you earlier, but he realized that this older technology was difficult and dangerous because of the rigidity of the Schindler scope.

On the impact of endoscopy:

The impact of fiberoptic endoscopy on practice was massive. Currently about 100-million endoscopies performed a year in the United States, about two thirds of them by GI doctors. Flexible fiberoptic endoscopy has had important impact worldwide in many medical and surgical fields.

On the discovery of the cause of ulcers:

Barry Marshall wrote in his note cards and some of his later publication “Everyone was against me, but I knew I was right.” So who was against him? The acid mafia, a powerful group of senior investigators who championed the idea that hydrochloric acid was the key to formation of stomach ulcers. When we were residents and fellows we had to know a lot about gastric hydrochloric acid secretion. So those who believed in the primacy of stomach acid were definitely strongly opposed to these Australian upstarts, Marshall and Warren. … Marshall and Warren were finally justified in 2005 when they won the Nobel Prize for Medicine. A couple of blokes from Australia who had not done a lot of research at all, with very little support. they used equipment and tools that were right at hand. This seems to be a study that could have been performed by almost anyone. But they were the first, and their persistence in the face of heavy opposition payed off.

Five days after Al finished the clindamycin, he developed diarrhea, an upset stomach, and pain in the lower abdomen. The diarrhea was severe, occurring up to 10 times per day. He called his doctor who tested his stools for C. diff. The result was positive. Treatment was started with 10 days of Flagyl (one of the same antibiotics taken by Jeannie) four times per day. By the fifth day, his diarrhea was almost gone and Al was ready to go back to work.

Five days after Al finished the clindamycin, he developed diarrhea, an upset stomach, and pain in the lower abdomen. The diarrhea was severe, occurring up to 10 times per day. He called his doctor who tested his stools for C. diff. The result was positive. Treatment was started with 10 days of Flagyl (one of the same antibiotics taken by Jeannie) four times per day. By the fifth day, his diarrhea was almost gone and Al was ready to go back to work.